Sometimes technology doesn’t make life easy for translators. Sometimes translators don’t make life easy for themselves either. I was recently trying to explain to a fellow translator why I always insist on receiving the actual formatted source text before starting work, but I think he thought I was just being awkward and a little bit old fashioned. I mean seriously, who, in this day and age, needs to see what a text will look like when it’s printed? He didn’t say as much but I could detect this young hipster’s incredulity at my “old-world” approach.

Now it might well seem old-fashioned and a little pernickity, but the fact that the files to be translated were in XML format and translated using a TM tool meant that, without the formatted source text, the translator was effectively translating blind. The same applies to any text you translate using translation memory tools.

A typical text in XML format

When you’re dealing with a text like this, it’s all too easy to miss out on the kind of contextual information that would otherwise help you to make appropriate translation decisions. If you can’t tell whether a segment is a caption for an image, a chapter heading or even an ordinary paragraph sentence how do you know what’s the best way to translate it? If you see the word Garderobe in the text, but can’t see the photograph that goes with it of a sign on a wall with the same word, how do you know not to translate it? You need to know what came before the sentence, what comes after it and what is around it before you can properly understand and translate it.

I always thought it was obvious that the context of a sentence is important when translating but apparently not everyone shares this view. But how do you explain a fairly nebulous and intangible idea like context?

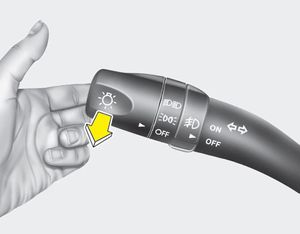

After a couple of rounds of emails, which didn’t seem to be getting us anywhere, I started thinking of how people communicate with each other by flashing their car headlights. This simple act of flicking a switch several times usually means “go ahead, you can pull out in front of me“. When the recipient of your good deed thanks you by flashing their hazard lights, you flash your headlights again to say “you’re welcome” – same sign, same interaction but slightly different context.

Other times you might flash your lights at someone who is driving too slowly, driving on the wrong side of the road, or at someone who cuts in front of you in fast-moving traffic and the meaning is similarly clear. Some people even warn other drivers about a speed camera by flashing their lights. The number and frequency of flashes may change but the same basic “utterance” has a number of different meanings depending on the context.

To complicate matters, this simple language (which has been likened in sophistication to the communication skills of insects) is also culture-dependent. In France, apparently, flashing your lights means “stay where you are, I am not letting you pull out in front of me“. But you can still understand what each flash means because, assuming you’re paying attention, you are aware of the context and what is happening around you.

Although it’s probably a silly example that has nothing to do with translation per se, it does sum up the idea of context. Pretty much anyone can translate a sentence, but not everyone can come up with the right translation at the right time. To paraphrase the late Miles Kington, knowledge is knowing that a tomato is a fruit; wisdom is knowing not to put it in a fruit salad. Let’s hope my translator friend figures it out too.

JodyByrne.com

JodyByrne.com